If you were to drill straight down into Mars, what would you find? Would the red planet reveal its true colors? Would you finally discover life on Mars? And how would drilling through Mars compare to drilling on Earth?

This is the Jezero Crater on Mars. And three and a half billion years ago, it looked very different. It used to be an ancient river delta that carried clay minerals into the crater lake. It might even have hosted Martian life.

Fast forward, and now the Jezero Crater has become a perfect landing site for NASA’s shiny new rover. Meet Perseverance. If I were to search for past lifeforms on Mars, this is the place I’d start looking, too.

Only instead of collecting rock samples, I’d send a rover to drill through the surface. What’s the worst that could happen?

Did you know Mars has marsquakes? They’re like earthquakes but on Mars. NASA’s Martian lander called InSight detected 480 of these marsquakes in 2020 alone. Luckily, there isn’t much out there to damage.

For us, these marsquakes are a good thing. They create seismic waves that our scientists can study. And based on these studies, they can theorize about the Martian interior.

But you and I would be doing this the hard way. We would drill through Mars to see what secrets it holds inside. If you started drilling through the reddish, iron oxide-abundant surface layer of Mars, the first thing you’d discover is that the interior is not so red.

But don’t be surprised. In 2012, NASA sent the Curiosity rover to Mars. It landed about 3,700 km (2,300 mi) from the Jezero Crater. Curiosity discovered that the layer beneath the surface of Mars is (VO – pause here) slate-blue. That’s because it contains high levels of silicon.

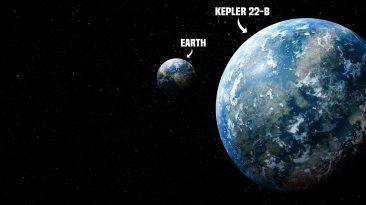

And as you drill, you should continue to expect the unexpected. The next discovery you’d make is the crust layer on Mars is thinner than the one on Earth.

Remember InSight? This little lander indicated that the Martian crust is only around 20 or 37 km (12-23 mi) thick, compare that to the Earth’s crust which is approximately 40-50 km (25-31 mi) thick under the continents.

If water still exists in liquid form on Mars, it could be several kilometers inside this crust. There are radioactive elements in the liquid mantle below the crust. These elements release geothermal heat through their decay. And it should be enough heat to melt thick sheets of subsurface ice.

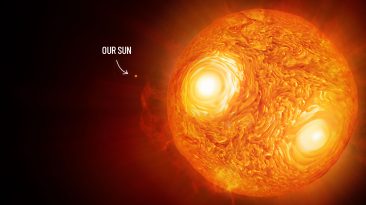

This geothermal heat could be why there was liquid water on Mars four billion years ago, even though the surface temperatures were below freezing. But enough theory, let’s keep drilling. Boring through Mars would be even harder than drilling through Earth.

The deepest we’ve ever drilled on Earth was 3.25 km (1.9 mi) 12.2 km into its crust. And that came with high budget costs, technical difficulties and plenty of bad luck. But on Mars, this would be an unimaginably tricky endeavor.

The InSight lander tried it before. But it encountered unexpected soil properties. The drill probe was trying to go 5 m (16 ft) deep but could only go a fraction of the distance before popping out.

Then there was Curiosity. It experienced a mechanical error. The drill feed mechanism that was supposed to move the drill bit forward wasn’t moving when commanded.

Luckily, scientists designed a new, more human form of Martian drilling. Now, the rover uses the force of its robotic arm to push the drill bit into the surface as it spins.

But don’t get your hopes high about reaching the mantle of Mars too soon. It took Curiosity the entire day to drill a mere 5 cm (2 in) hole. Based on that, going 5 km (3 mi) down would take you up to 300 years. And you’d need a bigger drill.

There’s still so much we have to learn about Mars. But maybe drilling isn’t the most effective way to do it. Especially since we still haven’t gotten very far into the crust of our planet. But we’ll leave digging into that story for another WHAT IF.

Sources

- “Jezero Crater – Perseverance Landing Site”. 2021. mars.nasa.gov.

- “Earthquakes and the Earth’s internal structure”. 2021. American Museum Of Natural History.

- “Surprise! First Peek Inside Mars Reveals A Crust With Cake-Like Layers”. Alexandra, Witze. 2020. nature.com.

- “You’re Going To Need A Bigger Drill. The Best Place For Life On Mars Is Deep, Deep Underground – Universe Today”. 2020. Universe Today.

- “What’s Mars Made Of? Researchers Simulate The Core Of Mars To Investigate Its Composition And Origin”. 2021. Sciencedaily.

- “NASA Puzzled As Insight Drilling Instrument Pops Back Out Of Martian Surface – Extremetech”. Whitwam, Ryan. 2019. Extremetech.