Venus, Earth’s closest planetary neighbor is one of the most extreme and hostile environments in the Solar System. With blistering temperatures, toxic clouds, and crushing atmospheric pressure, the idea of human settlement there seems like science fiction. And yet, some scientists believe it might actually be more hospitable for colonization than Mars.

But how could that be true? And what would it really take to survive and even thrive on this scorching world?

Let’s break down what the first 10,000 days of populating Venus might actually look like.

Day 1: The Robotic Phase Begins

Before any human sets foot near Venus, we would need to launch an extensive wave of robotic exploration missions. While past spacecraft like NASA’s Magellan and the Soviet Union’s Venera missions have given us glimpses of the Venusian landscape, it has been over three decades since the U.S. launched a dedicated mission to Venus.

New satellite projects in the 2020s and 2030s aim to fill in the gaps, collecting vital data on atmospheric chemistry, pressure, and terrain. As Noam Izenberg from NASA’s Venus Exploration Analysis Group points out, the only way to truly plan a colonization effort is by expanding our knowledge base, something we are only just beginning to do again.

Day 500: First (Fatal) Human Attempts

Imagine astronauts trying to land and explore the surface of Venus. The results would be grim.

Surface temperatures on Venus reach around 467 degrees Celsius (872 degrees Fahrenheit) hot enough to melt lead. Combine that with an atmosphere nearly 90 times denser than Earth’s, and it becomes clear that even the most advanced space suits or landing craft wouldn’t survive.

As Izenberg explains, it’s not a matter if you would die on the surface of Venus, but how. Would it be the heat? The pressure? The acidic clouds? The answer is all of the above.

Day 1,000: Terraforming Trials

Let’s assume we abandon surface settlement and try terraforming instead.

Theoretically, we could use genetically engineered microorganisms to absorb the carbon dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere. To reduce surface temperatures, massive orbital solar shades could be deployed to block or deflect sunlight. The idea is ambitious, and straight out of science fiction.

And for now, that’s where it belongs. As Izenberg bluntly states, “We don’t have the technology, the resources, or even the faintest idea of how to make Venus Earth-like.” If we could terraform a planet, we’d likely start with fixing Earth first.

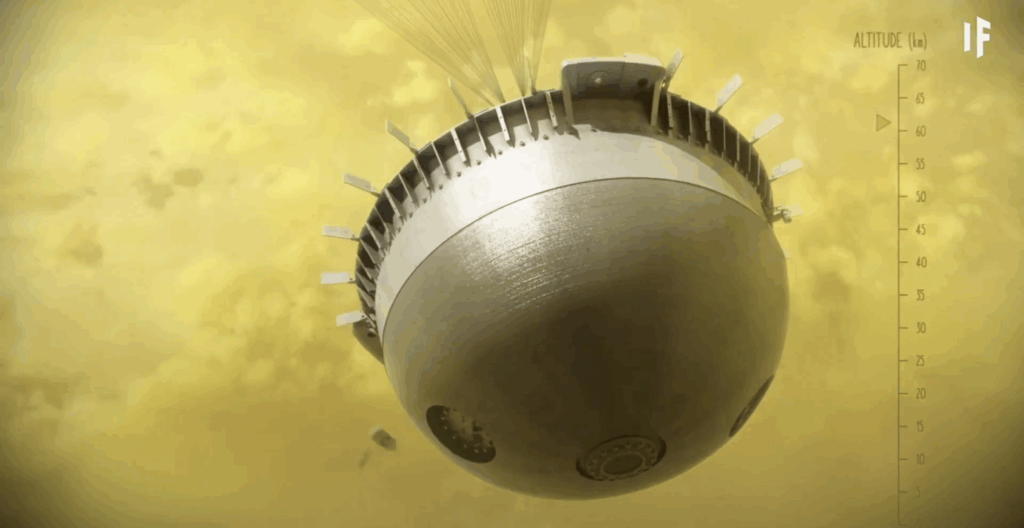

Day 2,500: Building Cities in the Clouds

So if the surface is off-limits, where could humans live on Venus?

About 50 kilometers (31 miles) above the surface lies an atmospheric layer that might actually be the most Earth-like environment in the Solar System. Temperatures there range from 20 to 30 degrees Celsius, and the atmospheric pressure is roughly equivalent to that at sea level on Earth.

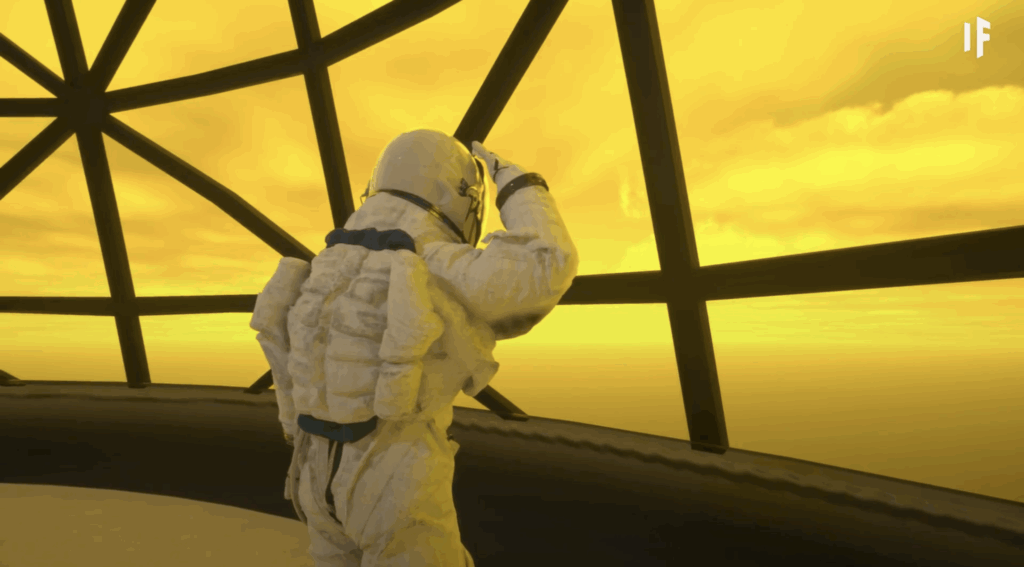

Enter the concept of cloud cities, floating habitats made from durable materials like Teflon and Kevlar. These massive blimps or platforms could house people, labs, and greenhouses, all connected by bridges and shielded from solar radiation by the thick Venusian atmosphere.

In this layer, it might actually feel like a warm spring day. That is, if you stay inside.

Day 5,000: Life in the Sky

After six years of cloud city living, humanity would be hard at work keeping these habitats operational. That includes building solar-powered systems, managing hydroponic food sources, recycling water and air, and constantly avoiding the threat of sulfuric acid clouds.

Not all areas in the upper atmosphere are hazardous, but the wrong location could expose you to acid that would burn through most conventional materials. Only high-grade materials like Kevlar could offer real protection.

Even then, the lifestyle would be intense. Days would be filled with maintenance, survival planning, and scientific research.

Day 10,000: A New Generation, But a Fading Dream

Three decades in, Venus might have a small population of astronauts, scientists, and maybe even a few children born in the sky. The infrastructure would be well developed, but the excitement? Not so much.

Living in a constant yellow haze, with few views of the planet below and little opportunity to go outside, would take a psychological toll. As Izenberg puts it, “You’d be living in a box, with most of your views through automated ports.”

While Venus’ upper atmosphere may be more survivable than its surface, long-term habitation would be isolating and monotonous. Over time, the dream of colonizing Venus might start to feel less like pioneering and more like confinement.

Is Populating Venus Worth It?

Despite the theoretical possibilities, Izenberg is clear: permanent habitation of Venus is unlikely and probably unwise. The dangers are too great, and the lifestyle too grueling.

However, this does not mean humanity should abandon the dream of becoming an interplanetary species.