One day, we want to take humanity into space. But why don’t we start small? Take one solar power station, 10,000 people, and 10 million tons of crumbled Moon rock, and you get a space habitat. A Stanford Torus

How would this habitat work? Who would be allowed to live there? And how would it help to reverse climate change on Earth?

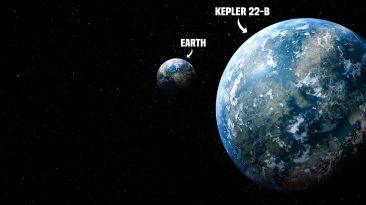

We’ve already hypothesized about living on an O’Neill cylinder, a Dyson Sphere, even a Matrioshka Brain. How would this habitat be any different? For one, it’s size. A Stanford Torus would be about 60 times smaller than an O’Neill cylinder, and it’s much, much smaller than a Dyson Sphere.

To build a Stanford Torus, we’d need to mine the Moon a little. The Moon is a perfect mining candidate, because it has oxygen in its rocks we could use to make a breathable atmosphere and manufacture water. It has silica we’d use for windows and solar cells. It also has aluminum that would work perfectly for construction. But of course, securing the materials is only a beginning.

We’d start assembling the habitat in space, between the Moon and the Earth. It would have to be close enough to the Moon so that we could easily transport the materials. It would also need to be far enough from the Earth that it wouldn’t fall into our planet’s orbit.

Our Stanford Torus would look like a bicycle wheel, and the spokes would join together at the center. The inhabitants would live in the tire section. But before we bring people in, we need to create a proper environment and life support.

To imitate Earth’s gravity, we’d make the habitat complete a full spin on its axis every minute. The centrifugal force would make up for the weightlessness you’d normally experience in space, because you don’t want things to float around.

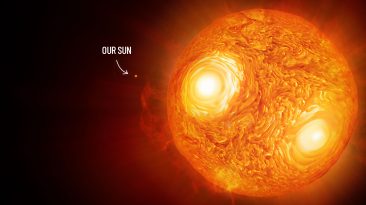

The habitat would get all its sunlight beamed down by a large mirror stationed directly over the hub at a 45-degree angle. It would direct solar rays into the smaller mirrors on the outer shell of the Torus. Those mirrors would also act as part of the shield from all the harmful cosmic radiation.

Living in this space habitat would be like living in a small town. There would be no skyscrapers, only labs, high-tech farms, and housing. Most of the people living on the Stanford Torus would be scientists or engineers, farmers or space construction workers. They’d take up a permanent residence on the Torus with their families, where they would live a sustainable colony life.

The population of the Stanford Torus would be limited to about 10,000 people. All the inhabitants would be strictly selected through extensive tests and training. But we wouldn’t just build the habitat for the sake of it. The Stanford Torus would benefit deep space research, and act as a maintenance and construction point for satellite solar power stations.

The solar power stations would provide for all the colony’s energy needs, and would have the potential to supply energy to Earth as well. We’d beam solar energy down with lasers or microwave emitters. Then we would collect that energy above the Earth’s atmosphere.

Having so much solar-generated power, we wouldn’t need to burn any fossil fuels. Give it enough time, and our planet might just recover from climate change. But all that wouldn’t be cheap. The cost of the Stanford Torus would come to some $900 billion. But we could minimize a large chunk of that cost by using reusable SpaceX rockets to send people to space.

Eventually, we’d start building more habitats, and explore more of the Solar System. We’d build a lunar base, and then set a course for Mars. But before you sign up on that mission, you need to have a good survival strategy in case something goes wrong. And we have a show for you that covers just that, to help you survive whatever awaits you.

Sources

- “Stanford Torus Space Settlement|National Space Society“. 2020. space.nss.org.

- “The Colonization Of Space”. 2020. space.nss.org.

- “Powering The Stanford Torus”. 2020. large.stanford.edu.

- “About The Space Station Solar Arrays”. 2020. NASA.

- “Mining The Moon”. 2017. Mining Technology | Mining News And Views Updated Daily.