Imagine a dry desert with endless sand dunes transforming into a lush, green tropical paradise before your eyes. This is the ambitious vision of terraforming the Sahara Desert, a project that could reshape the planet in ways both miraculous and alarming.

Such a massive transformation could help combat global warming by absorbing carbon and influencing rainfall patterns. Yet, it also carries risks, including ecosystem disruption and unforeseen shifts in global climate. Understanding the potential consequences requires examining both the possibilities and the challenges. Here’s a detailed look at what could happen and how it might unfold over the years.

Two Paths for a Green Sahara

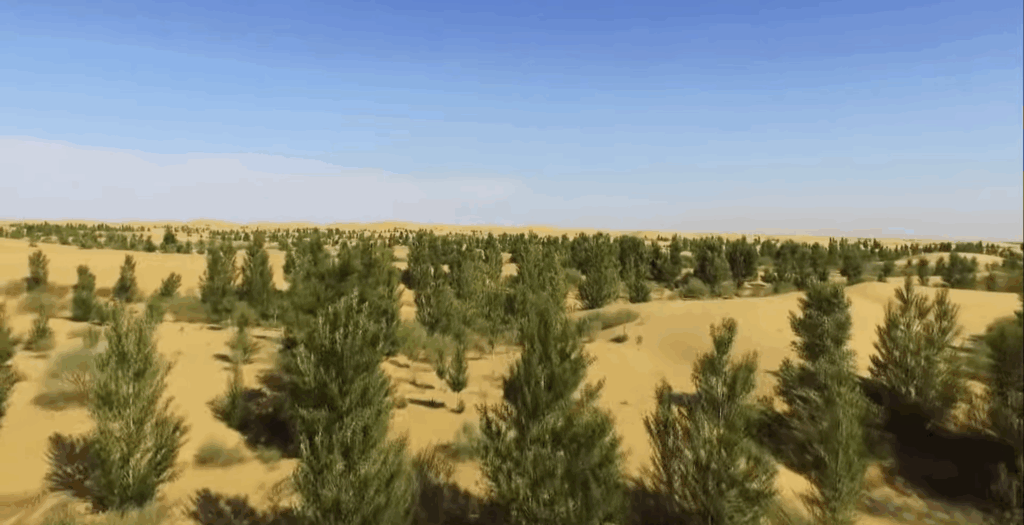

The Sahara could be transformed in several ways, each dramatically reshaping its landscape. One ambitious idea is to replace the desert with forests, covering its 9.8 trillion square meters with drought-tolerant trees that survive on about 500 millimeters of water per year. This could gradually create a subtropical climate that absorbs carbon, supports wildlife, and allows medicinal and food plants like aloe vera, passionflower, and cannabis to thrive.

However, the scale is unprecedented, and such a project could disrupt local communities and native species. A more realistic approach might mix forests, farmland, and grasslands, balancing human use, economic growth, and ecological stability.

The Water Challenge

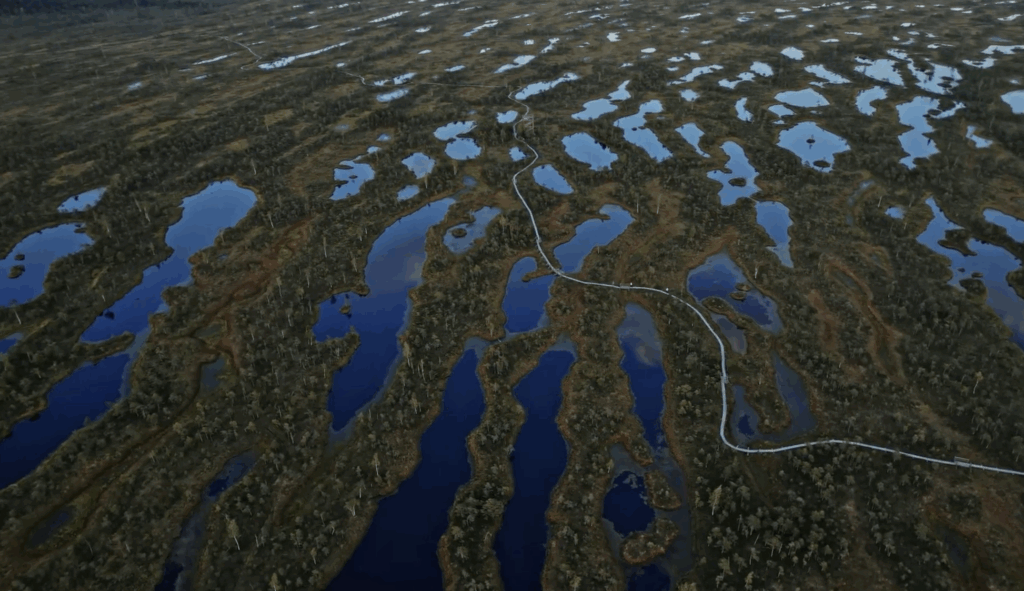

Water is the biggest obstacle to creating a green Sahara, as a fully forested desert would need about 4.9 trillion cubic meters per year, more than global consumption. Underground aquifers could supply water temporarily, but they would likely run dry within 30 years, threatening resources for countries like Sudan, Libya, and Egypt.

Seawater desalination could help, but it requires massive plants, pipelines, and energy infrastructure, with costs potentially reaching trillions of dollars. Solar power from the desert could supply energy, but long-term success would demand global cooperation, careful planning, and sustainable management. Without these coordinated efforts, even the most ambitious plans could fail to maintain water and ecological balance.

What Would the Timeline Look Like?

If the necessary resources, technology, and cooperation were available, the Sahara’s transformation could unfold over decades. Experts estimate a staged approach, with each decade building on the previous progress. From infrastructure construction to gradual planting and land management, the project would evolve carefully. Here is a possible decade-by-decade outline.

10 Years

The first decade would focus on building infrastructure. Desalination plants would be established along the coasts, pipelines mapped, and soil prepared for vegetation. Early plantings would occur near the ocean, where water access is easiest. Small-scale farms and experimental forests could also begin. Initial efforts would test the feasibility of sustaining plant life and preparing the land for larger-scale development.

20 Years

By the second decade, the water network would expand deeper into the desert. Trees, farmland, and grasslands would gradually spread, transforming the soil and influencing rainfall patterns. Vegetation would slowly shift the Sahara toward a subtropical climate. Carbon capture from new forests could begin helping mitigate global warming. However, these effects would only be meaningful if global emissions were simultaneously reduced.

50 Years

After 50 years, the Sahara could become a vast, green landscape. Yet new environmental challenges could emerge as forests and grasslands absorb more sunlight than sand, potentially increasing local temperatures. This paradox could mean that while carbon levels fall, heat could rise. Ecosystem management would need to adapt to unexpected climate shifts. Monitoring and adjustments would be essential to maintain the delicate balance between greening and overheating.

100 Years and Beyond

If fully implemented and maintained, the Sahara could stabilize as a thriving subtropical region. Forests, fertile farmland, and diverse ecosystems could coexist sustainably. Millions of jobs might arise from construction, maintenance, and agriculture, echoing initiatives like the Great Green Wall of Africa.

Tourism and research could further boost regional economies. Long-term success would depend on sustainable water use, careful ecosystem management, and continued climate stability.